Tawarruq

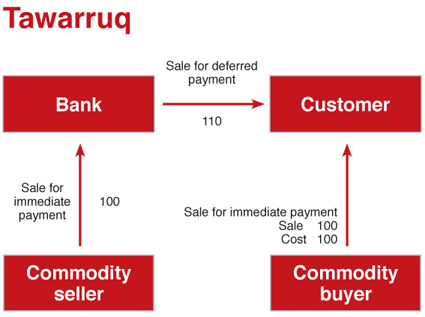

Tawarruq is the mode through which Islamic Banks are facilitating the supply of cash to their clients. The method consists on buying an asset and immediately selling it to a client, either directly or indirectly, on a deferred payment basis. The client then sells the same asset to a third party for immediate delivery and payment, the end result being that the client receives a cash amount and has a deferred payment obligation for the marked-up price to the Islamic Bank.

Islamic Banks use Tawarruq in the form of reverse Murabaha Reverse where the client requires a cash lump sum. The client buys an asset from the Islamic bank as in Murabaha, but rather than retaining the asset for use in its business, sells it to a third party. Generally, banks deal with brokers who provide agency services and the commodity always remain in the same place without transfer of ownership from the seller to the buyer; thus a number of conditions of a valid sale may be lacking in such transactions.

Furthermore, by way of Tawarruq a person can obtain cash without taking an interest based loan. In fact, Tawarruq is different from Bai al Inah that involves the sale and instant ‘Buy-back’ of an asset for a price higher than that for which the seller originally sold it. Bai al Inah is not valid according to vast majority of the Muslim Jurists and the mainstream theory of Islamic finance, as the goods are sold back to the same person from whom these were bought. Whereas Tawarruq is considered a hilah to get cash in the garb of trade using two contracts when the bank is really the financier and not the seller. Trade profit is permissible because the parties undertake commercial risks and add value in terms of facilitating the clients. Therefore, there must be a known time-gap between the sale of the commodity by the bank to the client and the resale of the same commodity in the market by the banks as agent of the clients. Otherwise, the Shari´ah conditions for sale and purchase of goods such as possession, offer and acceptance, etc. would not be fulfilled. If the sale and purchase are conducted in a single session and place at pre-agreed prices without any time-gap, the element of risk would be eliminated; this would contradictory to Shari´ah principles. Tawarruq is allowed by contemporary Shari´ah scholars on the basis of Necessity provided the commodity purchased is sold to any third party. If sale and purchase are conducted under two separate contracts, legally the transaction would not become usurious. However, resale to the same person is not approved by majority of the Muslim jurists and Shari´ah scholars as it would deemed as a “buy-back” arrangement prohibited under the Shari´ah rules. Another cautious condition could be required by some jurists for a valid Tawarruq is that the process involved should not be pre-agreed among the three contracting parties. However, in general, Islamic banks involve pre-agreement on purchase, sale and resale of goods giving a fixed rate of return for banks without any commercial risk. In fact, what happens, basically, is that the client makes the bank its agent to resell the asset for cash in the market from where the bank had made the purchase.

Islamic Banks use Tawarruq in the form of reverse Murabaha Reverse where the client requires a cash lump sum. The client buys an asset from the Islamic bank as in Murabaha, but rather than retaining the asset for use in its business, sells it to a third party. Generally, banks deal with brokers who provide agency services and the commodity always remain in the same place without transfer of ownership from the seller to the buyer; thus a number of conditions of a valid sale may be lacking in such transactions.

Furthermore, by way of Tawarruq a person can obtain cash without taking an interest based loan. In fact, Tawarruq is different from Bai al Inah that involves the sale and instant ‘Buy-back’ of an asset for a price higher than that for which the seller originally sold it. Bai al Inah is not valid according to vast majority of the Muslim Jurists and the mainstream theory of Islamic finance, as the goods are sold back to the same person from whom these were bought. Whereas Tawarruq is considered a hilah to get cash in the garb of trade using two contracts when the bank is really the financier and not the seller. Trade profit is permissible because the parties undertake commercial risks and add value in terms of facilitating the clients. Therefore, there must be a known time-gap between the sale of the commodity by the bank to the client and the resale of the same commodity in the market by the banks as agent of the clients. Otherwise, the Shari´ah conditions for sale and purchase of goods such as possession, offer and acceptance, etc. would not be fulfilled. If the sale and purchase are conducted in a single session and place at pre-agreed prices without any time-gap, the element of risk would be eliminated; this would contradictory to Shari´ah principles. Tawarruq is allowed by contemporary Shari´ah scholars on the basis of Necessity provided the commodity purchased is sold to any third party. If sale and purchase are conducted under two separate contracts, legally the transaction would not become usurious. However, resale to the same person is not approved by majority of the Muslim jurists and Shari´ah scholars as it would deemed as a “buy-back” arrangement prohibited under the Shari´ah rules. Another cautious condition could be required by some jurists for a valid Tawarruq is that the process involved should not be pre-agreed among the three contracting parties. However, in general, Islamic banks involve pre-agreement on purchase, sale and resale of goods giving a fixed rate of return for banks without any commercial risk. In fact, what happens, basically, is that the client makes the bank its agent to resell the asset for cash in the market from where the bank had made the purchase.

Musawamah

Musawamah is a different form of Murabaha, in which parties bargain over the price of goods to be traded without any reference to the price paid or cost incurred by the seller and where the seller is not obliged to disclose the cost price. While the seller may or may not have full knowledge of the cost of the item being negotiated, they are under no obligation to reveal these costs as part of the negotiation process. This difference in obligation by the seller is the key distinction between Murabaha and. All other conditions relevant to Murabaha are valid for Musawamah as well. Musawamah can be used where the seller is not in a position to ascertain precisely the original cost of the commodities being offered on sale.

Musawamah can also be either cash or a credit sale, but it is generally used as a credit sale, in which banks negotiate with clients on the price of assets to be sold by the bank, and paid by the client later. Banks add their profit margin to their cost but are not required to disclose the details of their cost price and their profit margin in any transaction.

Musawamah is the most common type of trading negotiation seen in Islamic commerce. Classical Muslim jurists generally preferred Musawamah over Murabaha for trading. It is considered as easier because Murabaha implies a trust reposed in the seller and requires detailed description to the buyer which could include a risk of some false. However, Musawamah as a financing mode for Islamic banks is a not as efficient as Murabaha. The absolute prices fixed for goods in the case of Musawamah, may lead to corruption and mismanagement at a micro level. While, in Murabaha, the Islamic bank managers price the goods by applying the profit margin or reference rate to their cost. Nevertheless, banks can Musawamah for large transactions, when it is difficult to determine the original cost of particular goods or a service, or when the goods to be sold comprise a pool of products.

Musawamah can also be either cash or a credit sale, but it is generally used as a credit sale, in which banks negotiate with clients on the price of assets to be sold by the bank, and paid by the client later. Banks add their profit margin to their cost but are not required to disclose the details of their cost price and their profit margin in any transaction.

Musawamah is the most common type of trading negotiation seen in Islamic commerce. Classical Muslim jurists generally preferred Musawamah over Murabaha for trading. It is considered as easier because Murabaha implies a trust reposed in the seller and requires detailed description to the buyer which could include a risk of some false. However, Musawamah as a financing mode for Islamic banks is a not as efficient as Murabaha. The absolute prices fixed for goods in the case of Musawamah, may lead to corruption and mismanagement at a micro level. While, in Murabaha, the Islamic bank managers price the goods by applying the profit margin or reference rate to their cost. Nevertheless, banks can Musawamah for large transactions, when it is difficult to determine the original cost of particular goods or a service, or when the goods to be sold comprise a pool of products.

Kafalah

Kafalah is a contract whereby a person accepts to guarantee or take responsibility for a liability or duty of another person. When it relates to an act, it is about ensuring the performance of a certain act, the failure of which may render the surety liable and responsible. In finance, the lender or the seller on credit can demand a security in form of Kafalah to which the seller could have recourse in the event of failure by the borrower to fulfil the obligation of payment for the goods.

In Islamic banking, there are generally two forms of contracts for guarantee and safe return of loans to their owners guarantee i.e. Kafalah and Rihn. They are both used to avoid any iniquities to both parties in the contract of loan, especially to the creditor. Mutual consent/agreement is the basis for validity of both the contracts as in other business transactions. In the contract of Kafalah, a contract is made between the Bank and another party whereby the Bank agrees to discharge the liability of a in the case of default. As a guarantor, the bank has the responsibility to honour the obligation of the debtor for whom a third party is given. As a surety, the guarantee will give the bank some form of collateral and pay a small fee for the services. The degree of suretyship in Kafalah should be known to all parties. However, it is not necessary for the guarantor to mention the exact amount of the debt guaranteed and it would be sufficient. Further more, Islamic banks can use different types of guarantees to secure their receivables, such as, Letter of Guarantee, post dated cheques, Promissory notes, Lien over cash deposits, Third party guarantee or Earnest money.

The creditor would have the right to demand payment from the debtor and the surety and if the debtor does not pay, the surety will have to make payment to the creditor. In case the surety is required to pay the liability, the debtor would then be bound to repay the surety. It is lawful to become surety of a surety; and it is possible to have a joint guarantee consisting on more than one surety for a single obligation. However, a person cannot furnish as guarantee the goods that are pledged to that person or the assets taken by that person on lease.

In addition, Kafalah is a non-commutative contract and the Shari´ah scholars do not allow any remuneration to be received for issuing financial guarantees. The reason why this is forbidden in Shari´ah, is that guarantor’s payment of the guaranteed sum will be similar to a loan generating a profit to the lender, which would involve Riba. However, some Islamic banks offers this service to its clients on a fee basis (Wakalah bil Ajr), they claims the right to seek fees representing actual administrative expenses. These fees for the services rendered by the banks should be commensurate with those charged by other banks. They will exclude the interest which accumulates from the date of and the date of actual settlement by the client.

In Islamic banking, there are generally two forms of contracts for guarantee and safe return of loans to their owners guarantee i.e. Kafalah and Rihn. They are both used to avoid any iniquities to both parties in the contract of loan, especially to the creditor. Mutual consent/agreement is the basis for validity of both the contracts as in other business transactions. In the contract of Kafalah, a contract is made between the Bank and another party whereby the Bank agrees to discharge the liability of a in the case of default. As a guarantor, the bank has the responsibility to honour the obligation of the debtor for whom a third party is given. As a surety, the guarantee will give the bank some form of collateral and pay a small fee for the services. The degree of suretyship in Kafalah should be known to all parties. However, it is not necessary for the guarantor to mention the exact amount of the debt guaranteed and it would be sufficient. Further more, Islamic banks can use different types of guarantees to secure their receivables, such as, Letter of Guarantee, post dated cheques, Promissory notes, Lien over cash deposits, Third party guarantee or Earnest money.

The creditor would have the right to demand payment from the debtor and the surety and if the debtor does not pay, the surety will have to make payment to the creditor. In case the surety is required to pay the liability, the debtor would then be bound to repay the surety. It is lawful to become surety of a surety; and it is possible to have a joint guarantee consisting on more than one surety for a single obligation. However, a person cannot furnish as guarantee the goods that are pledged to that person or the assets taken by that person on lease.

In addition, Kafalah is a non-commutative contract and the Shari´ah scholars do not allow any remuneration to be received for issuing financial guarantees. The reason why this is forbidden in Shari´ah, is that guarantor’s payment of the guaranteed sum will be similar to a loan generating a profit to the lender, which would involve Riba. However, some Islamic banks offers this service to its clients on a fee basis (Wakalah bil Ajr), they claims the right to seek fees representing actual administrative expenses. These fees for the services rendered by the banks should be commensurate with those charged by other banks. They will exclude the interest which accumulates from the date of and the date of actual settlement by the client.

Istijrar

Istijrar is an agreement where a buyer purchases a particular product from time to time on an on-going basis; each time there is no offer or acceptance or bargain. All terms and conditions are finalized in one master agreement. There are two types of Istijrar: A type whereby the selling price is determined after all transactions of purchase are complete; and a type whereby the selling price is determined in advance but the purchase is executed from time to time.

In the first type, the seller discloses the price of goods at the time of each transaction and the sale becomes valid only when the buyer possesses the goods. The sale and repurchase transaction takes place regularly. The amount is paid after all transactions have been completed. The seller may not disclose each and every time to the buyer the price of the subject matter, if the other party knows that it is being sold on market value. In the second type where the purchase price is not known, there may be a general acceptance between the buyer and the seller that whatever the price may be at the time of possession, it would be acceptable to the buyer.

As far as the use of Istijrar in Islamic banks is concerned, they are involved in four kinds of activities, namely Ijarah, Mudarabah, Musharakah and Murabaha. Istijrar can work with suppliers of the borrower. In this case, the Islamic bank enters into a Murabaha with the suppliers on the basis of Istijrar. It will purchase assets from them at a market price. Whenever the bank has a new client, it can purchase the assets from the suppliers on the basis of Istijrar and sell it onwards to the client on the basis of Murabaha. The client may then purchase the assets from the banks in tranches rather than at once and complete the whole purchase within the specified time period in order to complete the agreement. The terms and conditions of repeat sale could be of any normal cash or credit sales. An agreement may take place between the buyer and the supplier, whereby the supplier agrees to supply a particular product on an on-going basis, for example monthly, at an agreed price and on the basis of an agreed mode of payment.

A typical Istijrar transaction could be implemented where, for example, a car production factory approaches an Islamic bank seeking short-term working capital to finance the purchase of a commodity such as air-conditioning units. The bank purchases the units at the current price, and resells it to the factory for payment to be made at a mutually agreed date in the future. The price at which settlement occurs on maturity is contingent on the air-conditioning units' price movement from the day the contract was initiated to the maturity. Unlike a Murabaha contract, where the settlement price would simply be a predetermined price, the price of the Istijrar can be settled at any time before contract maturity. The price At the initiation of the contract, both parties can agree on the predetermined Murabaha price or an average price over the period. Normally, the bank would continue to deliver the specified units at the price known to the client, and the client would make payment on a monthly basis or as agreed between them. Separate offer and acceptance is needed for every consignment based on a formal from the client to the bank.

In the first type, the seller discloses the price of goods at the time of each transaction and the sale becomes valid only when the buyer possesses the goods. The sale and repurchase transaction takes place regularly. The amount is paid after all transactions have been completed. The seller may not disclose each and every time to the buyer the price of the subject matter, if the other party knows that it is being sold on market value. In the second type where the purchase price is not known, there may be a general acceptance between the buyer and the seller that whatever the price may be at the time of possession, it would be acceptable to the buyer.

As far as the use of Istijrar in Islamic banks is concerned, they are involved in four kinds of activities, namely Ijarah, Mudarabah, Musharakah and Murabaha. Istijrar can work with suppliers of the borrower. In this case, the Islamic bank enters into a Murabaha with the suppliers on the basis of Istijrar. It will purchase assets from them at a market price. Whenever the bank has a new client, it can purchase the assets from the suppliers on the basis of Istijrar and sell it onwards to the client on the basis of Murabaha. The client may then purchase the assets from the banks in tranches rather than at once and complete the whole purchase within the specified time period in order to complete the agreement. The terms and conditions of repeat sale could be of any normal cash or credit sales. An agreement may take place between the buyer and the supplier, whereby the supplier agrees to supply a particular product on an on-going basis, for example monthly, at an agreed price and on the basis of an agreed mode of payment.

A typical Istijrar transaction could be implemented where, for example, a car production factory approaches an Islamic bank seeking short-term working capital to finance the purchase of a commodity such as air-conditioning units. The bank purchases the units at the current price, and resells it to the factory for payment to be made at a mutually agreed date in the future. The price at which settlement occurs on maturity is contingent on the air-conditioning units' price movement from the day the contract was initiated to the maturity. Unlike a Murabaha contract, where the settlement price would simply be a predetermined price, the price of the Istijrar can be settled at any time before contract maturity. The price At the initiation of the contract, both parties can agree on the predetermined Murabaha price or an average price over the period. Normally, the bank would continue to deliver the specified units at the price known to the client, and the client would make payment on a monthly basis or as agreed between them. Separate offer and acceptance is needed for every consignment based on a formal from the client to the bank.

Jua'lah

Jua´lah is a unilateral contract promising a reward for the accomplishment of a specified task; this mode of financing is permissible from the point of view of the majority the Muslim jurists; it can be used for a number of banks’ services and activities. It is a relevant and useful contract for transactions where the subject not certain to exist or to come under a party’s control or where the required activity cannot be minutely. It can also be used for undertaking various activities such the extraction of minerals, finding out any lost asset or property, obtaining information or making a specific proposal for the offeror. Generally, Islamic banks provide fee-based services to their client on the basis of Jua´lah that include collection of debts, financing facility, asset management underwriting, Brokerage, etc

It is necessary to indicate the service and the reward in the Jua´lah contract. The reward should be known, valuable, permissible and deliverable. The reward can also be portion of the realised result. It can be paid in advance in full or in part before completion of the work. Though, the service would not be a legal obligation upon the worker and the entitlement to compensation for him will be contingent only upon execution of the contract, therefore, any advance payment has to be treated as ‘on account’ and not as a payment for the accomplishment of the specified task. Also, the worker is not entitled to a reward if Jua´lah is terminated unilaterally by either party before the commencement of work. If the contract is terminated by the offeror after the work is started, the offeror has to pay to the worker a market standard wage.

Jua´lah is different from Ujrah and Ijarah where financial compensation, such as wages, commission, rental, etc., is paid simply for using services or an asset. In fact, in Jua´lah, one party offers specified compensation to the worker who may be any specified person or the general public. In fact, an offer of Jua´lah can be issued to the general public in response to which any person can undertake the work. He can be anyone who has to realise a determined result in a known or unknown period. And while Ijarah contracts require that the work must be specified, Jua´lah is relevant for transactions where the subject of the required activity cannot be minutely specified such as bringing back a lost property from uncertain location. Also, unlike in Ujrah and Ijarah, the worker will not be entitled to any compensation for effort or time spent if the objective of Jua´lah contract is not realised.

Jua´lah can be comparable to Wakalah, when the worker is specifically designated; in that case he will have to undertake the work and may also involve others with the express consent of the offeror. The worker is considered only a trustee of any property or goods of the offeror in the possession of the worker; he is not legally responsible for any loss with the exception of any negligence, misconduct or violation of the terms of the contract. Moreover, an Islamic bank may play the role of the worker by signing a Jua´lah contract to provide a service. It may then carry out the work or have it carried out through another parallel contract involving a third party provided the first Jua´lah contract does not require that only the bank must undertake the work.

It is necessary to indicate the service and the reward in the Jua´lah contract. The reward should be known, valuable, permissible and deliverable. The reward can also be portion of the realised result. It can be paid in advance in full or in part before completion of the work. Though, the service would not be a legal obligation upon the worker and the entitlement to compensation for him will be contingent only upon execution of the contract, therefore, any advance payment has to be treated as ‘on account’ and not as a payment for the accomplishment of the specified task. Also, the worker is not entitled to a reward if Jua´lah is terminated unilaterally by either party before the commencement of work. If the contract is terminated by the offeror after the work is started, the offeror has to pay to the worker a market standard wage.

Jua´lah is different from Ujrah and Ijarah where financial compensation, such as wages, commission, rental, etc., is paid simply for using services or an asset. In fact, in Jua´lah, one party offers specified compensation to the worker who may be any specified person or the general public. In fact, an offer of Jua´lah can be issued to the general public in response to which any person can undertake the work. He can be anyone who has to realise a determined result in a known or unknown period. And while Ijarah contracts require that the work must be specified, Jua´lah is relevant for transactions where the subject of the required activity cannot be minutely specified such as bringing back a lost property from uncertain location. Also, unlike in Ujrah and Ijarah, the worker will not be entitled to any compensation for effort or time spent if the objective of Jua´lah contract is not realised.

Jua´lah can be comparable to Wakalah, when the worker is specifically designated; in that case he will have to undertake the work and may also involve others with the express consent of the offeror. The worker is considered only a trustee of any property or goods of the offeror in the possession of the worker; he is not legally responsible for any loss with the exception of any negligence, misconduct or violation of the terms of the contract. Moreover, an Islamic bank may play the role of the worker by signing a Jua´lah contract to provide a service. It may then carry out the work or have it carried out through another parallel contract involving a third party provided the first Jua´lah contract does not require that only the bank must undertake the work.