Murabahah

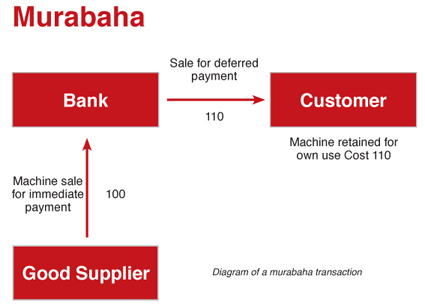

Murabaha is a form of sale where the cost of the goods to be sold as well as the profit on the sale is known to both parties. The purchase and selling price and the profit margin must be clearly stated at the time of the sale agreement. Payment of the Murabaha price may be in spot, in instalments or in lump sum after a certain period of time.

Murabaha has been adopted as a mode of interest-free financing by a large number of Islamic banks to finance the purchase of the consumer goods, intermediary or capital goods, real estate, raw materials, machinery and equipment. It may also be used for trade financing needs such as import of goods or pre-shipment export finance. However, the subject of Murabaha must exist and be in the ownership of the bank at the time of sale in a physical or constructive possession form; and these assets must be something of value that is classified as property in Islamic jurisprudence and must not be forbidden commodities. Debt instruments and monetary units that are subject to the rules of Bai´ al Sarf cannot be sold through Murabaha.

Murabaha has been adopted as a mode of interest-free financing by a large number of Islamic banks to finance the purchase of the consumer goods, intermediary or capital goods, real estate, raw materials, machinery and equipment. It may also be used for trade financing needs such as import of goods or pre-shipment export finance. However, the subject of Murabaha must exist and be in the ownership of the bank at the time of sale in a physical or constructive possession form; and these assets must be something of value that is classified as property in Islamic jurisprudence and must not be forbidden commodities. Debt instruments and monetary units that are subject to the rules of Bai´ al Sarf cannot be sold through Murabaha.

Islamic banks are required to take the genuine commercial risk between the purchase of the asset from the seller and the sale of the asset to the person requiring the goods. The bank is compensated for the time value of its money in the form of the profit margin. However, it is not compensated for the time value of money outside of the contracted term. In fact, the bank cannot charge additional profit on late payments; the asset remains as a mortgage with the bank until the Murabaha is paid in full; and there must not be any reference to the time of payment by the buyer to keep the transaction free from interest.

In addition, Islamic Banks should not simply provide funds through Murabaha; they have also to be involved in the trading process of their client’s business. They also need to ensure that the transaction is genuine and avoid the possibility of misuse of the funds by the client. In fact, the purchase price is paid directly by the bank to the seller or supplier, even though, the client may serve as the agent of the bank for onward. The purchase by the bank should be evidenced by invoices or other documents provided by the supplier to ensure that all conditions of a valid Murabaha have been fulfilled. Also the bank should arbitrarily inspect the purchased goods at their place of storage to ensure that the supplier and the client do not do any under-hand dealing, in fact, the client should not be a dual agent undertaking both the purchase and sale in a transaction.

Murabaha is not a loan given on interest. It is a credit sale that enables banks’ clients to make a purchase without having to take out an interest-bearing loan. The parties negotiate the profit margin to be paid on the cost of the original purchase, and not the cost price. If payment of the sale price is deferred, Murabaha becomes Muajjal, which is legal from the point of view of the Shari’ah. This one of the features that makes Murabaha attractive as a mode of financing in modern financing transactions: It is a sale transaction effected on the basis of deferred payment. The price should be fixed at the time of the original contract of sale and the due date of payment must be explicitly set. It has to be a fixed sum including the cost of goods to the seller and an agreed amount of profit over the cost that can also be based on a percentage of the cost price to the seller. The Murabaha selling price includes a mark-up agreed upon and added to the actual cost incurred by the seller; No additional profit can be paid over and above the contract price.

To determine the amount of profit on the purchase of the goods and onward sale to the client, the bank may take into consideration different factors such as the period for deferred payment. The difference in price is not meant as a reward for time to reflect sale In fact, the jurists agree that a seller can indicate two prices, one for cash and the other for a credit transaction, since it a genuine market practice ruled by supply and demand; but one of the two prices must be settled on at the time of contract. In fact, the credit price of a commodity may be more than its cash price at any one point of time, while, in a forward purchase, the price for future delivery of the goods may be less than the cash price. This practice is quite different from a loan or debt, on which any addition is prohibited.

A Murabaha transaction, as used by Islamic Banks is quite different from a traditional Murabaha. In fact, Islamic banks do not normally maintain an inventory of goods; rather they purchase the goods on the specific request of their clients. They take a binding promise to purchase from the client that he would purchase the goods when the same are acquired by the bank. This promise can be incorporated into the purchase request of the client to enable the bank to purchase the goods for the client, either directly or through an agent. The bank can keep an option to rescind the purchase for return of the goods within a specified period (Khiyar-e-Shart) as a risk management measure in the event that the client fails to purchase the goods from the bank. Khiyar can be used as a risk mitigation tool for the goods acquired at the risk and cost of the bank until the goods are sold to the client or returned to the supplier. In addition, Islamic banks can use different structures to provide financing by way of credit sales to their clients. The bank may purchase the goods direct from the supplier for sale onwards to the clients. Islamic banks can also conduct their trading activities either through the client acting as an agent of the bank or through third party agents appointed by the bank. Islamic banks may appoint qualified suppliers as third party agents to undertake the purchases as and when required. They may establish specific purpose companies, a limited number of the bank’s employees with relevant specialised expertise may be entrusted to trade in the goods required by their clients.

In the case of default by the client in the payment on the due date, the price selling price cannot be increased. However, contemporary Muslim jurists agreed that banks can impose a late payment penalty on delinquent clients. It may be a percentage on the overdue amount which cannot compounded. The penalty amounts must only be used for charitable purposes. Islamic banks can also ask for liquidated damages from the client through the courts, in case of default; and they can sell any held collateral without the intervention of the court.

In addition, Islamic Banks should not simply provide funds through Murabaha; they have also to be involved in the trading process of their client’s business. They also need to ensure that the transaction is genuine and avoid the possibility of misuse of the funds by the client. In fact, the purchase price is paid directly by the bank to the seller or supplier, even though, the client may serve as the agent of the bank for onward. The purchase by the bank should be evidenced by invoices or other documents provided by the supplier to ensure that all conditions of a valid Murabaha have been fulfilled. Also the bank should arbitrarily inspect the purchased goods at their place of storage to ensure that the supplier and the client do not do any under-hand dealing, in fact, the client should not be a dual agent undertaking both the purchase and sale in a transaction.

Murabaha is not a loan given on interest. It is a credit sale that enables banks’ clients to make a purchase without having to take out an interest-bearing loan. The parties negotiate the profit margin to be paid on the cost of the original purchase, and not the cost price. If payment of the sale price is deferred, Murabaha becomes Muajjal, which is legal from the point of view of the Shari’ah. This one of the features that makes Murabaha attractive as a mode of financing in modern financing transactions: It is a sale transaction effected on the basis of deferred payment. The price should be fixed at the time of the original contract of sale and the due date of payment must be explicitly set. It has to be a fixed sum including the cost of goods to the seller and an agreed amount of profit over the cost that can also be based on a percentage of the cost price to the seller. The Murabaha selling price includes a mark-up agreed upon and added to the actual cost incurred by the seller; No additional profit can be paid over and above the contract price.

To determine the amount of profit on the purchase of the goods and onward sale to the client, the bank may take into consideration different factors such as the period for deferred payment. The difference in price is not meant as a reward for time to reflect sale In fact, the jurists agree that a seller can indicate two prices, one for cash and the other for a credit transaction, since it a genuine market practice ruled by supply and demand; but one of the two prices must be settled on at the time of contract. In fact, the credit price of a commodity may be more than its cash price at any one point of time, while, in a forward purchase, the price for future delivery of the goods may be less than the cash price. This practice is quite different from a loan or debt, on which any addition is prohibited.

A Murabaha transaction, as used by Islamic Banks is quite different from a traditional Murabaha. In fact, Islamic banks do not normally maintain an inventory of goods; rather they purchase the goods on the specific request of their clients. They take a binding promise to purchase from the client that he would purchase the goods when the same are acquired by the bank. This promise can be incorporated into the purchase request of the client to enable the bank to purchase the goods for the client, either directly or through an agent. The bank can keep an option to rescind the purchase for return of the goods within a specified period (Khiyar-e-Shart) as a risk management measure in the event that the client fails to purchase the goods from the bank. Khiyar can be used as a risk mitigation tool for the goods acquired at the risk and cost of the bank until the goods are sold to the client or returned to the supplier. In addition, Islamic banks can use different structures to provide financing by way of credit sales to their clients. The bank may purchase the goods direct from the supplier for sale onwards to the clients. Islamic banks can also conduct their trading activities either through the client acting as an agent of the bank or through third party agents appointed by the bank. Islamic banks may appoint qualified suppliers as third party agents to undertake the purchases as and when required. They may establish specific purpose companies, a limited number of the bank’s employees with relevant specialised expertise may be entrusted to trade in the goods required by their clients.

In the case of default by the client in the payment on the due date, the price selling price cannot be increased. However, contemporary Muslim jurists agreed that banks can impose a late payment penalty on delinquent clients. It may be a percentage on the overdue amount which cannot compounded. The penalty amounts must only be used for charitable purposes. Islamic banks can also ask for liquidated damages from the client through the courts, in case of default; and they can sell any held collateral without the intervention of the court.

Concerns

Shari´ah scholars generally consider Murabaha to be a border-line technique because its transactions may give the appearance of a fixed-income loan with a fixed rate of profit determined by the profit margin agreed by the parties. However, the fixing of a profit margin per se is not a problem, as prices have to be fixed in all valid trade bargains and at no point money is treated as a commodity in the Murabaha transaction, as it is in a conventional loan. In fact, in Murabaha, the Islamic bank buys an item at one price and sells it to someone at a higher price, allowing them to pay the client for it over time. While in Riba, conventional banks lend someone some money and require them to pay back a greater value of money than what they borrowed.

Moreover, the exchange in respect of a loan, wherein any excess is prohibited, occurs between a commodity and its like, while in a Murabaha transaction, exchange takes place between two different commodities: money is first exchanged for goods purchased and then goods are sold for money. Therefore, the difference between the purchase price and the sale price does not amount to Riba and legitimizes the profit derived from trading. Goods traded in Murabaha should be real, they must exist at the time of the sale and in the ownership of the seller when selling to another party. Further, interest charged on a loan is payable to the lender unlike in a sale contract where the price is liable to change; if it rises, the purchaser gains on purchasing goods on deferred payment basis, but if the price declines, it is the seller who gains on selling the goods on deferred payment basis at a higher price.

In addition, the use of Murabaha implies a risk of destruction or loss of goods occurring during a period where the bank owns the goods acquired for their clients. Thus the mark-up could be justified by the liability for the goods assumed by the bank until the client purchases them at a higher price on a future date. Besides, the promise from the client to buy the commodity from the bank is not a legal binding; therefore, the client may go back on his promise and the bank risks the loss of the amount it has spent. The goods are also subjected to no acceptance by the client if there is any hidden defect.

Another concern in the light of the Shari´ah for using Murabaha is the pre-payment rebate. In fact, Shari´ah scholars may consider it similar to interest-based instalments sale techniques, where the rebate allowed for early settlement of a financing is intended to reflect a refund of unearned interest. In Murabaha, the rebate shouldn’t be already stipulated in the contract. Therefore, there is no commitment from the bank in respect of any discount in the price of a Murabaha transaction, the bank has discretion on whether to allow a rebate or not if the client makes an early payment. In any case, the profit on a Murabaha sale on a deferred payment basis is not based on a monetary value of time.

Moreover, the exchange in respect of a loan, wherein any excess is prohibited, occurs between a commodity and its like, while in a Murabaha transaction, exchange takes place between two different commodities: money is first exchanged for goods purchased and then goods are sold for money. Therefore, the difference between the purchase price and the sale price does not amount to Riba and legitimizes the profit derived from trading. Goods traded in Murabaha should be real, they must exist at the time of the sale and in the ownership of the seller when selling to another party. Further, interest charged on a loan is payable to the lender unlike in a sale contract where the price is liable to change; if it rises, the purchaser gains on purchasing goods on deferred payment basis, but if the price declines, it is the seller who gains on selling the goods on deferred payment basis at a higher price.

In addition, the use of Murabaha implies a risk of destruction or loss of goods occurring during a period where the bank owns the goods acquired for their clients. Thus the mark-up could be justified by the liability for the goods assumed by the bank until the client purchases them at a higher price on a future date. Besides, the promise from the client to buy the commodity from the bank is not a legal binding; therefore, the client may go back on his promise and the bank risks the loss of the amount it has spent. The goods are also subjected to no acceptance by the client if there is any hidden defect.

Another concern in the light of the Shari´ah for using Murabaha is the pre-payment rebate. In fact, Shari´ah scholars may consider it similar to interest-based instalments sale techniques, where the rebate allowed for early settlement of a financing is intended to reflect a refund of unearned interest. In Murabaha, the rebate shouldn’t be already stipulated in the contract. Therefore, there is no commitment from the bank in respect of any discount in the price of a Murabaha transaction, the bank has discretion on whether to allow a rebate or not if the client makes an early payment. In any case, the profit on a Murabaha sale on a deferred payment basis is not based on a monetary value of time.

Risk Management techniques

Murabaha mode of financing is adopted by the Islamic banks to satisfy a variety of financing requirements of their clients in various and diverse sectors. It can be used to provide finance for the purchase of consumer durable or to finance the purchase of machinery, equipment and raw material for manufacture, etc. This mode is highly suitable for providing short-term working capital in financing projects. It can also be used for import and export trade as well as for local trade.

However, Murabaha may not be suitable for housing or other long term investments in economies with a high rate of inflation. The reason for that is that the bank might face a greater risk in the possible return if the general rate in the market increases owing to inflationary pressures. Murabaha can still be used for mortgage financing for longer periods ranging in economies where inflation is not a major issue. Also, Murabaha is not the right mode to provide financing for the purchase of easily perishable items.

Nevertheless, Islamic banks must bear a certain amount of risk associated with Murabaha transactions in order to legitimize their returns. They use some techniques to manage and mitigate each type of the common risks. In order to ensure that the bank's gains are above all suspicions of Riba, the bank reduces Shari´ah non-compliance risk by making direct payment to the supplier, it requires the invoice from the seller for the goods purchased, the date of which not before the offer and acceptance is carried out and not later than the declaration and it also arranges for the random physical inspection of the goods. This technique seeks to avoid that the client has already purchased the goods and subsequently wants the financing to make payment to the supplier. The bank can also obtain Takaful Insurance to reduce in-transit risk of destruction or loss of goods occurring without the agent’s negligence. The bank may ask the client to provide security through any assets of the client and stipulates a penalty payment clause in the contract that in the event of payment defaults. Murabaha does not allow additional charges in case of instalments. The amount of the Murabaha price remains unchanged. Long-term Murabaha may be avoided to guard against rate of return risk.

Moreover, the bank may obtain a performance bond from the supplier to prevent from non-performance risk by the supplier where he may not perform an obligation to supply the goods. The client can undertake to guarantee the performance of the supplier. Similarly, for the non-performance risk by the client where the he may refuse to purchase the goods when acquired by the bank at the client’s request, the bank should secure a promise from the client to purchase the goods. Furthermore, the bank can ask for Hamish Jiddiyah to recover its possible loss. Hamish Jiddiyah can also be used to prevent from a legal risk in case the client does not purchase the goods, as the initial agreement is only a promise by the client to buy and for the bank to sell; the bank who purchases the goods required by the client, may have to be involved in litigation.

In addition, there is a greater fiduciary risk where the client is appointed as agent to purchase and take possession of the goods on behalf of the bank; this could result in the client failing to administer the trust and agency accounts. To guard against such risk, bank may provide in the Murabaha contract that the client would be liable for any such loss. There is also a liquidity risk, since Murabaha receivables are debts payable on maturity. Therefore, they cannot be sold at a price different from the face value in a secondary market if the repayment date has to be extended. Similarly, if the client is unable to pay the amount on time, which is essentially a credit risk, it can give also rise to a liquidity risk for the bank until the payment is made by the client.

However, Murabaha may not be suitable for housing or other long term investments in economies with a high rate of inflation. The reason for that is that the bank might face a greater risk in the possible return if the general rate in the market increases owing to inflationary pressures. Murabaha can still be used for mortgage financing for longer periods ranging in economies where inflation is not a major issue. Also, Murabaha is not the right mode to provide financing for the purchase of easily perishable items.

Nevertheless, Islamic banks must bear a certain amount of risk associated with Murabaha transactions in order to legitimize their returns. They use some techniques to manage and mitigate each type of the common risks. In order to ensure that the bank's gains are above all suspicions of Riba, the bank reduces Shari´ah non-compliance risk by making direct payment to the supplier, it requires the invoice from the seller for the goods purchased, the date of which not before the offer and acceptance is carried out and not later than the declaration and it also arranges for the random physical inspection of the goods. This technique seeks to avoid that the client has already purchased the goods and subsequently wants the financing to make payment to the supplier. The bank can also obtain Takaful Insurance to reduce in-transit risk of destruction or loss of goods occurring without the agent’s negligence. The bank may ask the client to provide security through any assets of the client and stipulates a penalty payment clause in the contract that in the event of payment defaults. Murabaha does not allow additional charges in case of instalments. The amount of the Murabaha price remains unchanged. Long-term Murabaha may be avoided to guard against rate of return risk.

Moreover, the bank may obtain a performance bond from the supplier to prevent from non-performance risk by the supplier where he may not perform an obligation to supply the goods. The client can undertake to guarantee the performance of the supplier. Similarly, for the non-performance risk by the client where the he may refuse to purchase the goods when acquired by the bank at the client’s request, the bank should secure a promise from the client to purchase the goods. Furthermore, the bank can ask for Hamish Jiddiyah to recover its possible loss. Hamish Jiddiyah can also be used to prevent from a legal risk in case the client does not purchase the goods, as the initial agreement is only a promise by the client to buy and for the bank to sell; the bank who purchases the goods required by the client, may have to be involved in litigation.

In addition, there is a greater fiduciary risk where the client is appointed as agent to purchase and take possession of the goods on behalf of the bank; this could result in the client failing to administer the trust and agency accounts. To guard against such risk, bank may provide in the Murabaha contract that the client would be liable for any such loss. There is also a liquidity risk, since Murabaha receivables are debts payable on maturity. Therefore, they cannot be sold at a price different from the face value in a secondary market if the repayment date has to be extended. Similarly, if the client is unable to pay the amount on time, which is essentially a credit risk, it can give also rise to a liquidity risk for the bank until the payment is made by the client.